Why not to ‘tuck the tailbone’ in a yoga class

16 December 2015

A couple of ideas on having a more pelvic-floor-friendly yoga practice

It is quite common to hear yoga teachers saying ‘Tuck the tailbone under’ when they want to initiate action from the core (mulabandha). This might be useful sometimes, especially working with people who don’t have much awareness of their pelvic floor and thinking of tucking the tailbone under can help them access the muscles their brain doesn’t ‘talk to’. But the tucking hint is used way too much and often unnecessarily. Some yoga styles even encourage keeping the tailbone tucked under in most poses, for stability.

There are a couple of things to think of before using this clue. ‘Tuck the tailbone under’ could be:

- Misleading — The pelvic floor lift in yoga (mulabandha) is meant to come from lifting at the central tendon of the pelvic floor (between the openings) and not from the action of the tailbone. Telling students to tuck the tailbone makes them over-activate the wrong muscles — gripping the gluteals, tightening the hamstrings, the deep hip rotators and the very back of the pelvic floor, without lifting the central tendon.

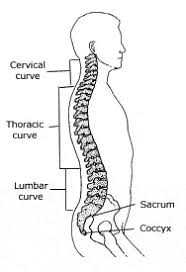

- Changing how your core fires — When you curl the tailbone under trying to stabilise the body, tightening your glutes and the hips together with the rectus abdominis flattens the lower back. This interferes with the synergy of the transversus abdominis (TrA) in front and the lumbar multifidus muscles in the back. The multifidi can’t work effectively when the back is flat. This is why a lot of people end up with back pain after classes that focus on core strength.

- Shortening your pelvic floor over time — keeping the tailbone under decreases the space between the pubic bone and the tailbone shortening the pelvic floor. Continuously contracting the pelvic floor while keeping it short will over time pull the sacrum into the bowl of the pelvis. Doing more strengthening work with your tail tucked under will make the pelvic floor even shorter and tighter, but not stronger. Unlike the TrA that (as a purely stabilising muscle) can work for longer periods of time, the pelvic floor lifts when we need an extra burst of energy and then releases to its full length. Keeping it lifted at all times would cause muscle fatigue.

A more pelvic-floor-friendly way to perform mulabandha, would be to try to initiate the lift from midway in between the openings without tucking the tailbone.

This way we can contract the pelvic floor muscles both eccentrically (as they lengthen) and as they shorten (concentric contraction).

To identify the right muscles, instead of focusing on the action of the tailbone I find it useful to pay attention to the action of sitbones, which with the lift of the pelvic floor come closer and with the release slide apart.

There is no need to actively squeeze the sphincters but just allow the area midway between the openings to gently lift. I usually say ‘Lift from the base of the torso’. This way we can promote the toning action of the pelvic floor, without overdoing it.

The next step could be to use mulabandha only as an exception and instead focus on stabilising the torso from front and back — organically activating TrA and lumbar multifidus muscles as we move. An extra lift from the pelvic floor could be added only when needed to ‘energise the movement’. Dance educator Hubert Godard uses this model to promote a fluid, responsive stability in movement, as opposed to keeping tension in the centre of the body. This could be beautifully applied to the postural practice of yoga too.

TrA naturally activates as you use Ujjayi breath. Or you can consciously activate it, especially in the case of people with lower back injuries or weak abdominals. Doug Keller uses a nice hint for TrA activation, saying ‘Imagine pulling the drawstring on a pair of sweatpants tighter’.

I also like to add a clue on top, saying ‘Imagine your pelvic bowl as a bowl of soup. Can you keep the soup level, not spilling either forward or back?’. This way we can make sure there is no tucking under, and the pelvis is in a neutral position.

Your core ability to fire depends on the position of the pelvis and the ribcage.

When you line up the pelvis and the ribcage on top of each other as a default, the diaphragm and the pelvic floor nicely sit on top of each other and all layers of the abdominal muscles, the muscles along the spine and the sides of the torso are at the length where they can fully contract — balancing the spine and providing enough stability for each movement.

Neutral spine = neutral pelvis + ribcage centred on top + head on top.

Restoring an upright, aligned torso with a neutral spinal curvature as a default, we can allow the stabilising muscles to maintain their optimal lengths and have enough leverage to generate force to support the body dynamically.

This way we won’t need to change the configuration of the pelvic joints (tuck the tailbone under) to add the extra oomph.

Please don’t take me wrong, tucking the tailbone is not bad in itself and please by all means do it as a part of your varied movement diet! But there is no need to use it as a default when practising yoga or living our lives.